Alisha + Alysha’s return to ritualism and healing

Written by Alisha Maryam and Alysha Nelson

Alisha + Alysha’s return to ritualism and healing

Following its acclaimed premiere, Gadis Ayu Terakhir (GAT) returned to Camden People’s Theatre in September, describing the importance behind a return to the ritualistic.

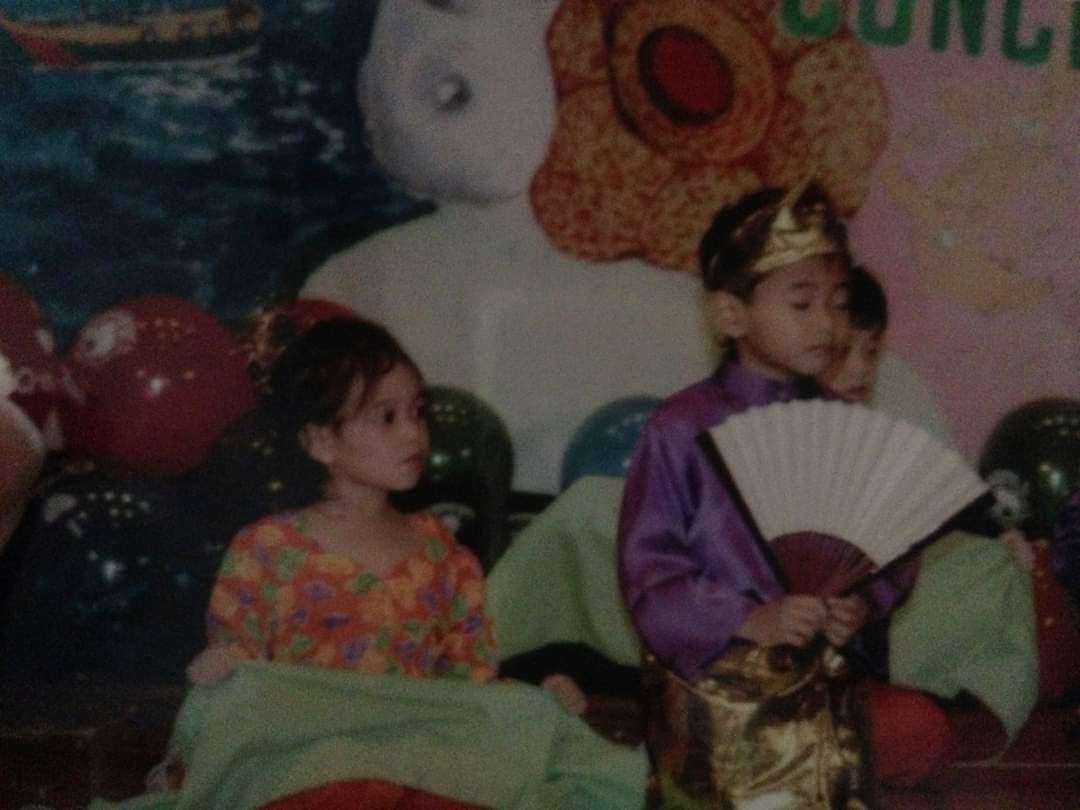

We connected while studying Drama, bonding over mutual feelings of being lost and an involuntary detachment to our cultural identity. As such, we sought to create theatre to platform marginalised and diasporic voices. Using traditional Malay art forms (Wayang Kulit and Mak Yong), we reimagined the legend of Mahsuri, highlighting Malaysia's lost (read: repressed) culture of healing and ritualism.

Islamisation in Malaysia

The legend of Mahsuri tells the story of a beautiful young woman living in Langkawi (a popular island in Malaysia) who was unjustly accused of adultery and subsequently executed by her community. In her dying breath, Mahsuri whispered a curse, condemning Langkawi to a desolate wasteland for seven generations.

In GAT, the story of Mahsuri is retold as an allegory behind rampant intra-cultural objectification within Malaysia’s society. The term ‘intra-cultural objectification’ refers to the subconscious denying or shaming of one’s culture that is rooted in a loss of identity. We felt the story of Mahsuri powerfully reflected the colonial hangovers which currently dictate modern Malaysia.

Currently, there exists very little documentation of Malaysia’s cultural traditions in the pre-Islamic and pre-colonial era. While much of this erasure can be traced back to colonial conquests, Islamisation has also played a big part in the legislative banning of cultural rituals. Particularly in the northern parts of Malaysia, practices like Wayang Kulit (Malaysian shadow puppetry) and the UNESCO protected Mak Yong (a traditional form of healing through story-telling and dance), were disallowed due to their history of being rooted in Hinduism.

There is a common misconception that British colonialism comes with the pattern of Christian missionary efforts, but the opposite is true when it comes to Malaysia. Historian, Khairudin Aljunied, describes it as ‘colonial Islamisation’:

“For most British administrators and scholars, Islam was but a veneer of the minds and hearts of the Malays that therefore provided a strong explanation for Malay indolence. From that assumption, they held that Islam in Malaysia could be easily secularised and a duality in systems, thought, and practices could be introduced to make Muslims more receptive to British rule”.

With Malaysia’s ethnically Muslim-Malay community taking up more than 50% of the population, Muslim elites were given material and hierarchical gains that would hold symbolic roles in helping the British expand their reach in Malaysia. These were the same elites who mobilised and formed the United Malays National Organisation, that essentially campaigned for Malay supremacy, leading the multiethnic coalition that governed Malaysia’s independence. While they stand as an example of interethnic political cooperation, it also institutionalised the role of ethnicity in Malaysian politics, creating racial and political polarisation. It was this imbalance in power dynamics that emphasised the importance of Islam in Malaysia, erasing the nuances that came with its culture during the pre-Islamic era.

Why was this important in the creation of GAT?

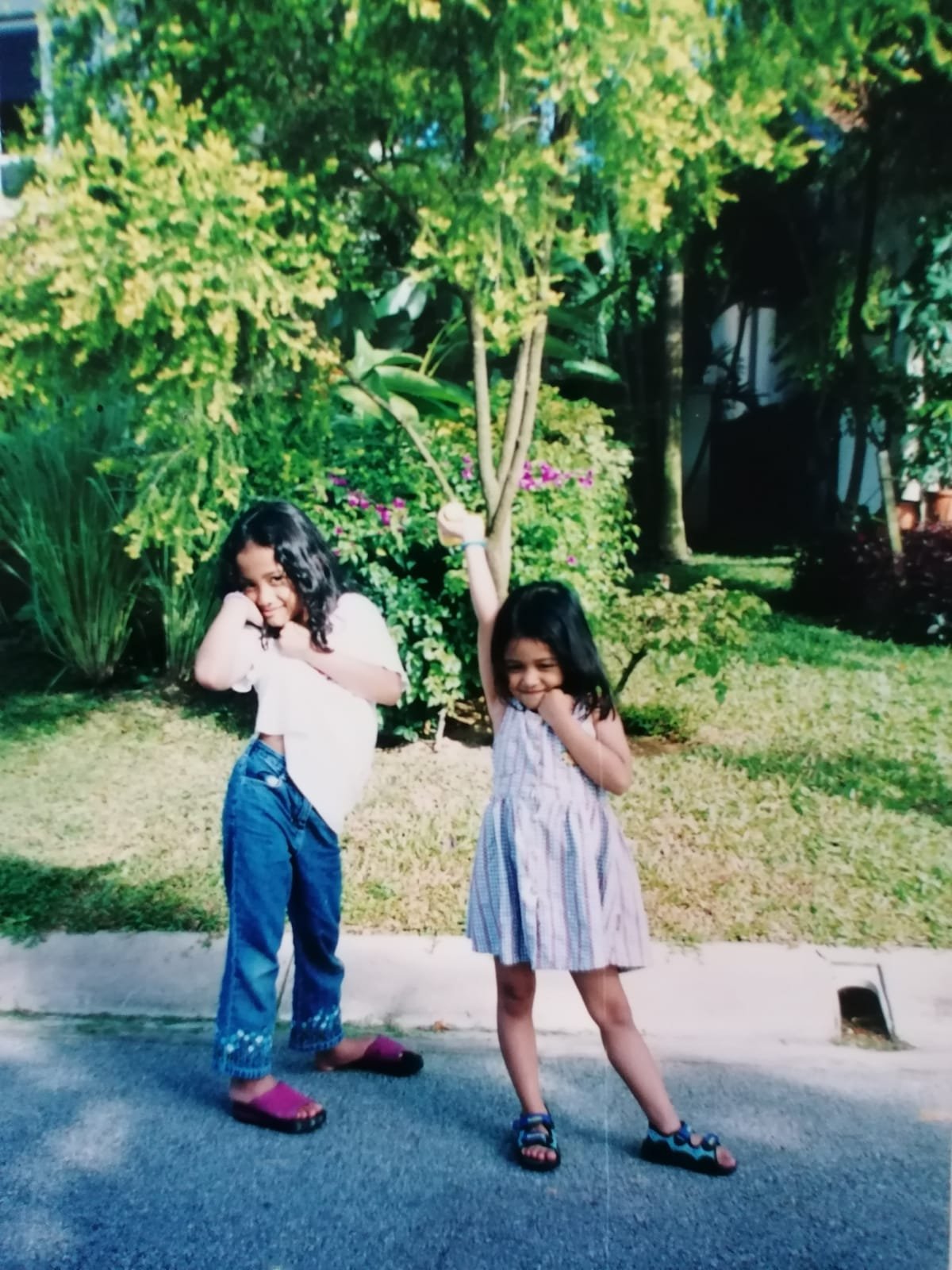

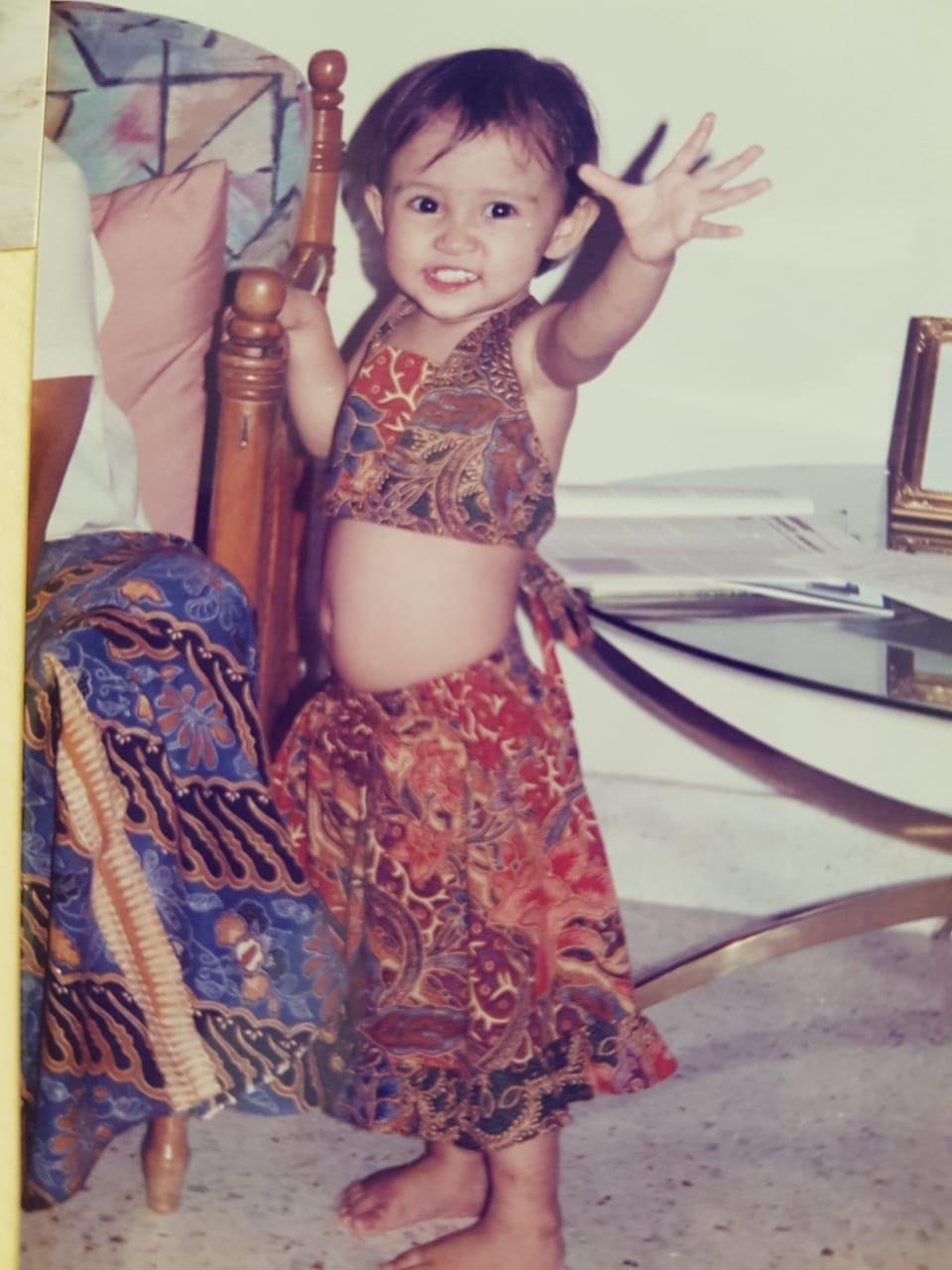

Despite this polarisation, Malaysia’s ethnic and cultural diversity can be felt deeply within its society. This diversity becomes even more apparent within its diasporic community, particularly for those that emigrate to the West. We felt this juxtaposition between cultural diversity and racial polarisation was a big factor in how we were raised. Growing up celebrating the various cultural holidays that have been ingrained in Malaysia’s social calendar, our palettes were influenced by the rich blend of Chinese, Indian and Malay cuisine. Following this, our affinity towards belonging was rooted in our acclimation to “community” in Malaysia.

A feeling that is discussed in GAT is the feeling of being misplaced and misunderstood. In our case, this was rooted in their desire to reconnect with the parts of our culture that celebrated healing and spirituality, an aspect of Malaysian history that was essential to our culture, yet lost in Malaysia’s everyday society. For those that reject the emphasis on religion in Malaysia, it can be hard to feel at home without being accused of having an ‘inauthentic’ Malaysian identity.

Malaysians are taught (in schools and society) of a very specific version of history - one that is rooted in racial separation. British colonialism was painted with a stroke of kindness and traditional Malaysian practices were overwhelmed with the focus on religion and depictions of “jins” and black magic. For those that choose not to believe this narrative, it can be easy to fall into a mind-set of not being a real Malaysian: “why am I the only one seeing the beauty in our ancient practices?” We believe that this feeling of rejection can be explained in the loss of the nation’s spirituality - it created a natural inclination towards finding a sense of identity in the ritualistic.

Eddin Khoo, founder of Pusaka, a non-profit that focuses on the preservation of ancient Malaysian practices argues that, “these traditions are not a matter of performance. They are deeply spiritual, the individual spirit and community spirit. Of course, in more recent times, the word ‘spirit’ has become so contentious, but these are therapeutic and healing traditions that are necessary for a community’s well-being.”

When creating GAT, the question for us then became, is there a sense of catharsis that has been gate-kept from us due to the absence of these spiritual practices?

Navigating a cultural haze and finding a cultural balance

This is what Gadis Ayu Terakhir aims to explore. For the Malaysian diasporic community, it can be so easy to forget your sense of identity based on what society and the country’s colonial hangovers tells you. Intra-cultural objectification manifests as entire societies blaming themselves for the erasure of their culture. It allows them to believe that the features and traditions they were born into are inherently barbaric; it creates a feeling of loss and a longing for a community; it might even trap you in a cultural haze where you believe you’re superior because you’re not ‘Asian Asian’, you’re palatable and inoffensive - ‘an undetectable other’.

GAT places importance on cultural practices that prioritise spirituality - a return to a sense of healing and togetherness that once made Malaysia a true community in its core. We believe that using traditional practices such as Wayang Kulit and Mak Yong is the only way to tell this story accurately. GAT exists to legitimise feelings of loss - it was created to conjure a sense of safety in learning about our history. It was created to ensure a part of our ancestry stays alive, despite efforts to destroy Malaysia’s rich past.

Excerpt from film used during Alysha and Alisha’s performance.

Keep up with the development of Gadis Ayu Terakhir by following @gattheatre on Instagram or reach out on gat.theatre@gmail.com

To keep up with Alisha and Alysha’s journey’s, follow them on @alishamaryam and @alyshanelson