The Architecture of Identity: Carrying legacy through CalEarth

Words by Neena Rouhani

Sheefteh Khalili’s father built homes for Mars.

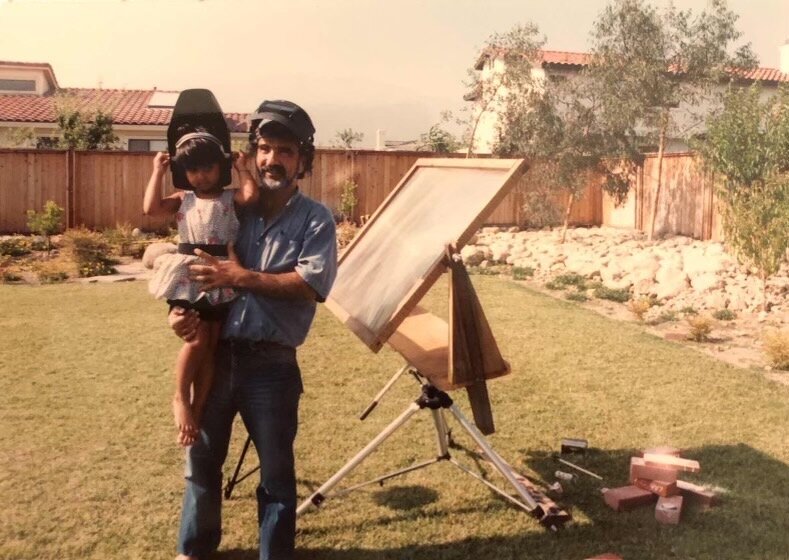

At age six, she spent weekends wandering through the deserts of southern California, 7,500 miles from her native Iran. She climbed mounds of dirt and piles of deformed bricks, discovering little treasures hidden in heaps of trash. Her father, renowned architect Nader Khalili, surveyed the grounds nearby, visualising what he would eventually transform into a micro-community of otherworldly dome-shaped homes, originally built for the moon and Mars.

Bit by bit, the barren hills of earth, metal and clay that were a 6-year-old Sheefteh’s playground became the CalEarth Institute, a non-profit organisation dedicated to finding solutions for the global housing shortage that leaves over 150 million people homeless. Through his sustainable, low-cost dome structures, Nader pioneered a new wave of home design that revolutionised earth architecture.

CalEarth was Nader’s life’s work and after his sudden passing, it became Sheefteh’s. Today, CalEarth centers the Khalili children—Sheefteh, 36 and Dastan, 48—the way that their father once did. It serves as a guide and reminder of their Iranian roots, humanity’s greater purpose and Nader’s timeless vision of an ethical and equitable future for the world’s most marginalized.

Stepping foot beyond the gates of CalEarth, the world suddenly feels still. The non-profit’s campus is 80 miles from Downtown Los Angeles, yet feels galaxies apart. Aside from the earth crackling beneath soles of shoes, the gentle rise and fall of the human breath and melodies sung by birds fluttering above, silence envelops the institute’s curious visitors.

For the last 12 years, Sheefteh has expanded CalEarth alongside her brother Dastan, drawing interest from Vogue Magazine, the Los Angeles Times, CNN, HGTV’s Tiny House Hunters, and fashion designers like The Elder Statesman. Every year, CalEarth attracts over 2,500 visitors, eager to tour the grounds, build SuperAdobe domes and deepen their understanding of Nader’s utopian vision. Today, there are SuperAdobe homes in countries all over the world including Nicaragua, Morocco, Madagascar, Portugal and the Khalili family's native Iran.

While many liken the grounds to scenes from Star Wars, Nader’s inspiration came from the earth-toned, rural desert villages of Iran, where he spent five years developing designs for the domes now scattered across CalEarth’s campus and around the world.

“People that have been to Iran...they're like ‘this really reminds me of Bam or Yazd’, because that's where the inspiration came from,” explains Sheefteh. “There’s something about [CalEarth]...it just draws you in.”

Although born and raised in California, Sheefteh’s Iranian heritage deeply informed the trajectory of her professional career. In 2017, she received her PhD in sociology, focusing primarily on racial and ethnic identity. Due to the pivotal role of her parents’ migration story in her own identity formation, Sheefteh researched the ways in which immigrant narratives shape the identity of their U.S.-born children. “The stories passed down through our families are how you and I were able to learn what it is to be Iranian,” she explains.

Her dissertation, titled “Caucasians on Camels: Iranian American Intergenerational Narratives and the Complications of Racial & Ethnic Boundaries,” consists of interviews with Iranian immigrants and their children, analyzing how the U.S. experience shapes first-generation Iranian-Americans’ racial identity, compared to their Iran-born and raised parents. In the opening pages of the dissertation, Sheefteh wrote a dedication to her mother “for her unwavering support” and to the memory of her father, “for too many reasons to count.”

After completing her studies, Sheefteh stepped away from sociological research and delved into the unknown world of administration, advancing from an entry-level research analyst to the Chief of Staff of Health Affairs at UC Irvine in three years. “[My professional success] is not because I got a PhD,” says Sheefteh. “It’s because of running CalEarth and because of my dad.”

From childhood, Nader taught Sheefteh to never settle for normal. At age three, she stood curiously alongside her father as he set fire to adobe vaulted structures for dazzled audiences. Her Lhasa Apso, Sugar, had her own Rumi Dome doghouse, a mini version of the dome Nader constructed at Cal-Earth. As a junior in college, Nader brought Sheefteh and Dastan to India, where they brushed shoulders with the country’s Prime Minister and various dignitaries at an award ceremony overlooking the Taj Mahal, where he was receiving a prestigious architecture award.

“[CalEarth] was his number one, his quest, his vision, and he was so focused on it that we all had to be part of it,” explains Sheefteh. “Because I don't know that he knew how to be about anything else.”

Because of his complete dedication to CalEarth, Nader wasn’t at soccer games and school functions, something that Sheefteh accepted early on. “I don't know that I ever thought there could be an alternative so I didn't question it,” she says.

Sheefteh’s unconventional life was sometimes a source of embarrassment during her younger years, but as she grew older, she became more aware of the profound impact her father had on her life. “I grew up with somebody who taught me to have a quest that's bigger than myself,” she says. “To think outside the box and be in service to others with the work that I do.”

Sheefteh describes the moment that marked the beginning of her father’s metamorphosis: his 3-year-old son’s footrace. “The story goes that one day he took my brother Dastan to the park,” she says. There, Nader encouraged Dastan, who was the smallest of the children playing, to compete against the others. “He kept coming in last place and he was so frustrated that he came to my dad crying,” says Sheefteh. “And he said, ‘I want to race alone.’”

Nader reluctantly agreed. He drew a line, counted down, and Dastan was off. Soon, his running slowed to walking, as he began collecting items along the way. “He brought a leaf from a sycamore tree and then he went around again, and brought a flower.”

Observing Dastan, Nader questioned society’s fixation on competition and the incessant need to race against others. At that moment, he decided to forge his own finish line, in a one-man race.

“If you race alone, you can meet and exceed your own expectations over and over,” says Sheefteh. “And you're always in first place.”

Image by Devin Williams

As detailed in his memoir, Racing Alone, Nader left his position as an esteemed urban developer, bought a motorcycle and ventured into rural Yazd, Bam and Varamin, spending time with villagers and studying their homes, made up of earthly elements. After five years and copious servings of rich, black Persian tea sipped beneath towering fruit trees, Nader figured out the formula. He mastered an impenetrable structure that could withstand nature’s twists and turns, made up of the very elements surrounding it: earth, water, fire and air.

One year following the 1979 Iranian Revolution, Nader and his family left their homeland forever. With his blueprints and newfound purpose in hand, he ventured to California, where both Sheefteh and CalEarth would come into existence.

Conducting tours on CalEarth’s campus, Sheefteh recites every detail of Nader’s story without a moment’s hesitation. Her mind is an index of stories, dates, names and places—an encyclopedia honoring her father’s life.

In our interview, she mentions the exact title of his 1988 proposal to a NASA symposium on building on the moon and Mars, which marked the beginning of CalEarth. She remembers the number of minutes NASA gave him to present his proposal, eight, and for the Q&A that followed, five. She recites the specific Persian poems he repeated to himself in times of uncertainty, the dates of every major turning point in his life and the complex emotions invoked in him, all with the same calm conviction her father had.

“Certain things in this story were pure magic,” says Sheefteh. She noted that NASA provided the highest level of security clearance to her Iranian national father in order for him to visit a U.S. government-run research facility during a time of severe political hostility between the two countries.

“His quest was so clear and so pure that any obstacle or challenge that came before him, there was always a way through or around,” she explains. Within her tone and enthusiasm, Sheefteh conveys the divinity woven throughout her father’s life.

Sheefteh describes Nader as having been a deeply spiritual person. “He grew up in a very devout Islamic family,” she says. “He pulled the essence out of it, I think more through Rumi and the spirituality and faith in God.”

For Iranians, poetry permeates religion, music and daily life. Ancient poetry is passed on from generation to generation, often as enigmatic advice from elders addressing the woes of their grandchildren, children, nieces and nephews. For Nader, the poems came as soft lullabies every night from his grandmother. Poems written by Saadi, Hafez, Rumi and Ferdowsi dating back one thousand years, made a home in a young Nader’s consciousness.

“If he was worried about something in his architecture or in his work, he would go to the poetry to find a gem of wisdom,” says Sheefteh. Nader later compiled and translated over 500 of his favorite Rumi poems from Farsi to English, now published across five books.

The verses passed down from her great-grandmother have become a treasured source of wisdom for Sheefteh. She often revisits the poems her father shared, his stories, books and films to find her way. Sheefteh recently transformed her father’s translations into a three book series on love, friendship and spirituality.

Image by Devin Williams

Nader was the sun and the moon for CalEarth. For his children, he was real-life magic, their guiding force, voice of reason and catalyst for purpose. In 2008, on his 72nd birthday, everything began to unravel.

“I flew down from San Francisco to surprise him,” Sheefteh explains. “And he was coughing, coughing, coughing, it was putting a lot of strain on his body.” Concerned about his weak heart, Nader’s family took him to the hospital, discovering he was sick with pneumonia. After a few days, Sheefteh returned to San Francisco, where she was wrapping up her Master’s degree.

One week later, Sheefteh received a call from her brother to return home immediately. Panicked, she rushed from class to the airport. “My body was in shock and I remember feeling really clammy,” she says. “He was in really bad shape.”

Three days later, Nader took his final breaths, leaving behind a shell-shocked Sheefteh and Dastan struggling to mourn their crippling loss, while keeping CalEarth above water. “I was 23 when my dad died. Within a year, I was running a nonprofit with my brother with no experience, no one to help us,” she explains. “It was this absolutely devastating experience.”

In the following months, Sheefteh frequently returned to CalEarth to guide visitor tours and take care of administrative tasks, reliving her heartbreak over and over again. “It was just heavy,” she says. “I’m trying to go to West L.A. on the weekends with my friends and be this early twenties person. Meanwhile, there's sandbag manufacturing crises, we have staffing problems, issues with city ordinances.”

While CalEarth has seen plentiful success, every year following Nader’s passing Sheefteh says the organisation has faced a significant obstacle. “I gotta tell you that COVID, of all of them, was the best because I was like, this isn't my fault,” she jokes. “We're shut down. There's no money. It's not my fault!”

Seven years following Nader’s passing, Sheefteh stepped foot in her native Iran by way of the Tehran Imam Khomeini International Airport, for the first time since she was four.

Between CalEarth, the support of friends and family, and attending her father’s burial, Sheefteh found a semblance of acceptance. However, for her family thousands of miles away in Iran, closure was a distant concept. Finally reunited with Sheefteh after 25 years, Nader’s family began to fully realise their loss.

“I'm literally in a mehmooni and the tears are just coming down my face,” she explains. “They wanted to cry with me because they didn't ever get to do it. They didn't ever get to grieve him.”

Throughout her time in Iran, Sheefteh became increasingly aware of the way space is held for community members who emigrated from Iran, never to return again. “You know how Iranians always say jaat khali? They meant we've held their space empty for them since [they emigrated],” she says. “It's not like they've moved on. Nobody's moved on. They just hold all of these empty seats at the table.”

Sheefteh hopes to soon revisit and publish her research on the Iranian diaspora. “Who I am is because of what my parents went through,” she says. “My whole identity is built around who my dad was.”

While happily dedicated to the continuation of her father’s legacy, Sheefteh strives to define herself outside of CalEarth. “I've been pushing so that I can find the space to have the rest of my life,” she says. “So I can have CalEarth and it can hold all the space it needs, but that I can also create a boundary around it and some distance.”

Outside of her job and work with Cal-Earth, Sheefteh runs what she jokingly calls an “Involuntary Mentorship Program,” providing practical support to uplift the women in her life. She says that once someone tells her their goals, she will make sure they are achieved. “The further I go, the more I learn, the more people I want to bring with me,” she explains. “I never want to be so far forward from the pack, because that means that I stopped giving back.”

Like father, like daughter.

For more by Neena and more on CalEarth, visit: